|

Good breeze. Remember to prep as much as possible at the dock: ie- staysail sheets and running backstays in place before leaving the dock.

4/9/21 to 4/11/21 night crossing to Los coronados with christian, katarina and victoria, diane4/12/2021 WHAT WE LEARNED:

VICTORIA: 1 - The most important consideration when at anchor is to be ready to leave within minutes. This means ensuring jacklines are down, cockpit lines are organized with no floating lines in the water, the ignition key is stowed in the ignition (yellow float tucked into the plexiglass), and other relevant preparations are taken before going below deck. 2 - I learned how, when, and why to flush the generator with fresh H20 - How Follow these steps:

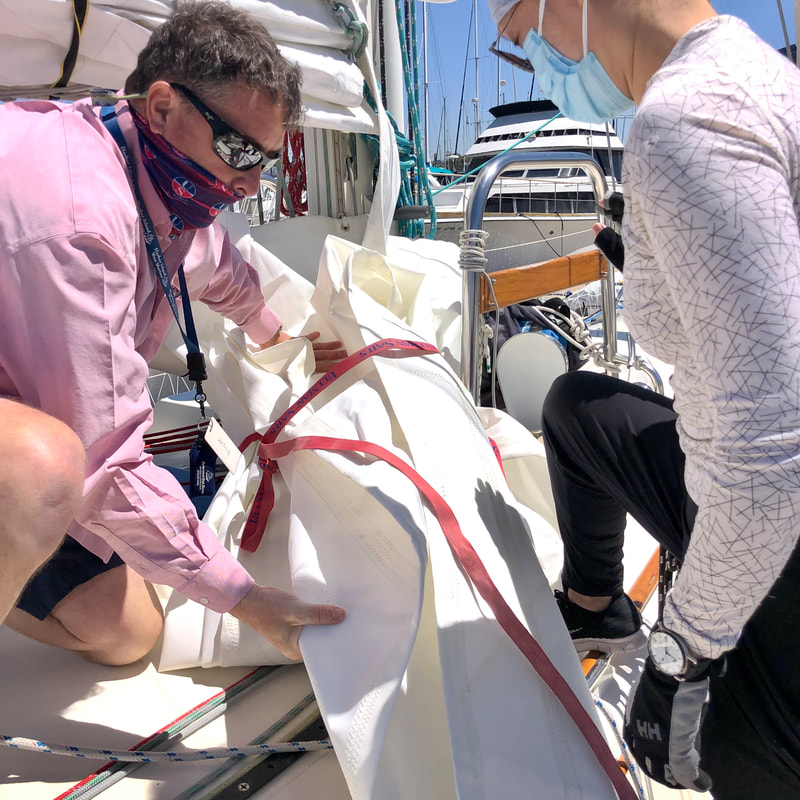

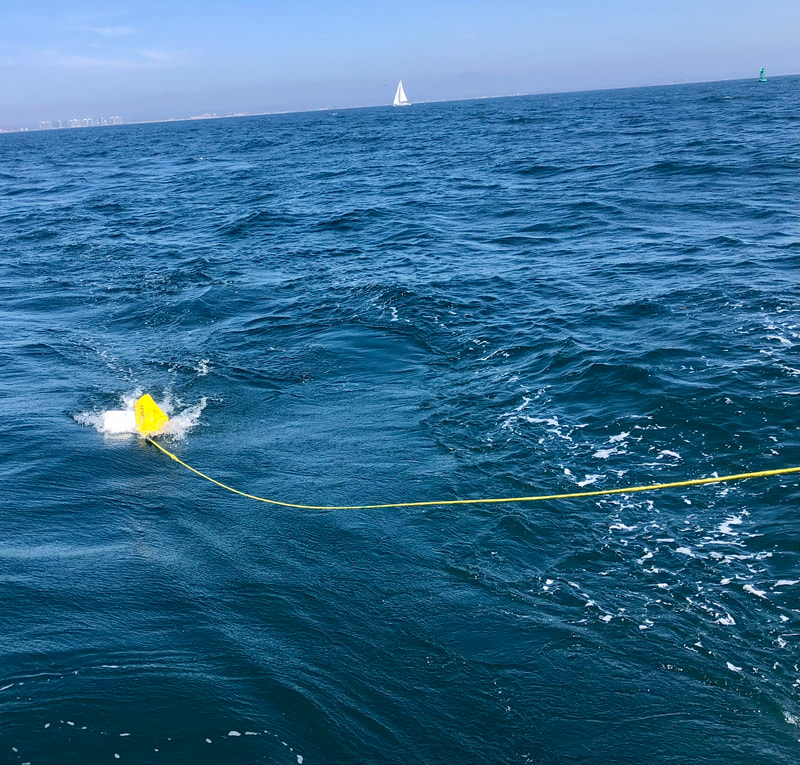

When When returning to dock, if the generator has been used for any significant amount of time (i.e. after a weekend cruise). Why If you don't rinse the generator with fresh water, the saltwater that runs through it to cool the system while in use will have a corrosive effect on the generator, leading to performance issues and reducing it's lifespan. Q for Diane: If at sea for an extended period of time (e.g. a 3 week ocean crossing), how frequently should this be done? Answer: Done after each voyage. 3 - a simple thing that should seem obvious but isn't inherently part of some of our 'checklists', but to ALWAYS do a visual check to ensure there are no lines in the water before turning on the engine. 4 - when packing provisions, do not bring disposable plastic packaging; bring in reusable containers for food storage bags (take from the galley if advanced coordination is possible). KATARINA: 1. Become more aware of your communication style. A pause can be perceived as ignoring or not engaging with other types of communicators. Say, "I'm thinking this through." or "I don't know." 2. Adjust your communication style to the situation. Ask questions when there is space and time, not when things are chaotic. 3. Follow commands but also remember your personal knowledge. Listen to instruction but don't forget steps in between. 4. The head pump works better than you thought. Pushing the lever helps bring water in. Pulling the lever firmly suctions the contents out, including the stubborn floaters :-D 5. Being Captain is not easy! Captain must have keen situational awareness, and always keep a running checklist of people, tasks, and timing according to the current situation and next anticipated move. 6. "Right-of-way" is a bad word! Use "stand-on" vessel instead; maintain your course and speed if you are the stand-on vessel. 7. Indicate clearly with big turns when you are the "give-way" vessel. Turn hard to starboard, to clearly indicate to the stand-on vessel that you see them. 8. Keeping a vigilant watch is essential and even more important at night. Other vessels may change direction, so keep a constant lookout and know the rules. 9. Make a call and say it outloud. Vocalize your thoughts so the rest of the crew knows what you are thinking. DIANE: 1. IF YOU DO NOT KNOW WHERE SOMETHING BELONGS ...ASK 2. PUT THINGS BACK WHERE THEY BELONG 3. DON'T HIDE THE CHOCOLATE! 4. SAY THANK YOU WHEN YOU RECEIVE FEEDBACK 5. LISTEN, LISTEN, LISTEN 6. FILL THE TEA POT BEFORE BED AND USE THE MANUAL FOOT PUMP AT NIGHT 7. SHOW WHERE THE HIGH WATER ALARM AUDIO SWITCH TURN OFF IS - NEXT TO COMPANION WAY STAIRS 8. WHEN YOU TURN OFF THE PROPANE, SOLENOID, HEATER ANNOUNCE IT TO THE CREW 9. WHEN CLIMBING ONTO THE BOAT WITH THE LIFE SLING, REPEL ON THE SIDE OF THE HULL 15 TO 20K WINDS, OVERPOWERED, HEAVED TOO AND EASED THE MAIN TO SLOW THE BOAT DOWN, RAN OVER THE FLOATING LIFE SLING LINE, WRAPPED THE GENOA. GREAT DAY FOR LEARNING AND WORKING TOGETHER.

. I was in a POB training class yesterday and it occurred to me that our current procedure puts undue risk upon the rescuer and risks a 2nd POB. Let me outline this nonlinear problem below).

Current Procedure: 1. Identify POB, turn the boat around. 2. Throw lifesling and circle the POB. 3. Upon the POB grabbing the lifesling, turn off the engine. 4. Take the Topping Lift from the aft end of the boom and bring forward to the windward midship shrouds, tie off. 5. Pull in the lifesling to the windward side of the boat. 6. Lower the topping lift to the POB, POB attaches to lifesling 7. Using electric winch at the cockpit, raise the POB on board. I found a few issues with this. The first being the complexity of the procedure. Though there are a few more pressing matters. Step 4: Removing the Topping Lift from the aft end of the boom. Doing this from within the cockpit requires standing above the lifelines. In heavy weather conditions (when a POB is more likely to occur), the boom may swing or move with waves and wind. If the sail is up then removing the topping lift wont impact the boom too much, but under motor the topping lifts as the primary counterforce to the mainsheet in stabilizing the boom. Regardless, a crew member must put their body above the lifelines and reach upward to remove the topping lift shackle, which is a screw in the shackle. I find this both dangerous and time consuming for even at a flat sea as yesterday, it is difficult to remove and a slip in balance would mean falling overboard or being injured in the cockpit. This is my primary concern in our POB procedures. Some solution ideas: In pondering this yesterday we came to a few ideas. The first is to use the 3rd line point at the top of the mast to rig a POB line, running to the cockpits 4th (and currently empty) break. The end of the line would be shackled to the bottom of the mast so when the rescuer has pulled in and tied off the lifesling they can retrieve the line from the bottom of the mast and hand it to the victim. Another potential solution would be in a quick release topping lift with a line hanging on the boom for its release. Step 5: Bringing in the lifesling with victim. Yesterday I asked the question if it was best to move the boat to the POB or the haul the POB towards the boat if the boat was under sail. Regardless the boat must be stopped in a heave to or by dropping the sails. If the life sling is thrown while under sail, the helmsmen could drop the main fairly quickly (just open the halyard break with the halyard ready to run free), though the jib is a two person job or a long one person job. Presuming the sails are dropped, the engine can be turned on and circles can be turned around the victim. Assuming the worst, a 2 person crew with one going overboard in rough seas, what actions should the helmsmen take? In thinking about this I've come to the following set of values to best form our POB procedure. - It should be simple, so that crew in crises can remember it and perform it well. - We should add as little risk to the rescuer as not to allow for a double POB during the rescue of the first. - The procedure should not leave room for questions. The current procedure does. - The procedure needs to account for nighttime POB. (A possibly more advanced second procedure). Although we can't have a 0% chance of rescue failure or error as Diane points out, I think we can increase the likelihood of success incredibly. I find that having a good POB procedure also allows for the crew to remain calm during its execution as they can trust the method over the instinctive feeling of doom. As it stands if I were to fall off the boat at night I think I would be rescued, but I think there would be incredible tension on the boat and I would spend considerable time on. the water. The current procedure took us about 10 minutes to conduct with new crew, with an experienced crew I could imagine it taking 7 minutes at minimum. My final thought is that the POB procedure should have an after rescue medical checklist/care list. The moments after rescue the victim is possibly sustaining a wound, in shock, cold, or a mixture of these. I think an easily accessible medical checklist like the boat check on or off would allow for the crew to again trust a system in times of crises. Something along the lines of, drying and removing victims wet clothes, check for head wound, give these medicines for these ailments etc etc. I think a general medical procedure based on best field medicine practices would also be good to have. Thus from small knife cuts to broken bones we can assure we went through the best course of action (e.g. do not move victim, evaluate victim, if A then B, else if conduct C etc etc) Looking forward to your thoughts on this matter. -Christian |

|